Jergling's Postmortem

In June, I joined, but did not submit an entry to Indie City All-Stars 2025. I entered the jam with a mechanic that I wanted to try building, and without even a fuzzy picture of time management, completeness or the learning curve involved in making a long-run jam game. I had just started using Godot, after not making any interactive software since college, and it did not go well. I created something, but it couldn't really be called a game, and it wasn't something I wanted to share.

This time, a week before the jam started, I reached out to all the people I had good feelings about on the Indie City Discord who were looking for teams. I got near-immediate buy-in from everyone I contacted, and we were ready to go a week early with ideas burning holes in our cranial basins. We all agreed, nothing made before the jam would end up in the final work. Dani made around 4 times as much music before the jam as during, trying to narrow down the sound. I programmed and scrapped a whole navigation system, but learned what structure the real thing would need. I think we all read The King In Yellow. We were extremely prepared for the jam to start.

The first week was sort of lost to me. I was definitely learning a lot about Godot again, and I was dangerously unemployed, but while I might have been working on the game all day, every day, I can't exactly say what I did. I had this idea for the game to be claustrophobic and unnecessarily archaic in design, so I was researching Macintosh adventure games where the hardware could only handle a subwindow's-worth of graphics and the rest would have to be text. I also wrote this when debugging raycasting:

Camilla: You, sir, should unmask. Stranger: Indeed? Cassilda: Indeed it's time. We have all laid aside disguise but you. Stranger: I wear no mask. Camilla: (Terrified, aside to Cassilda) No mask? No mask!

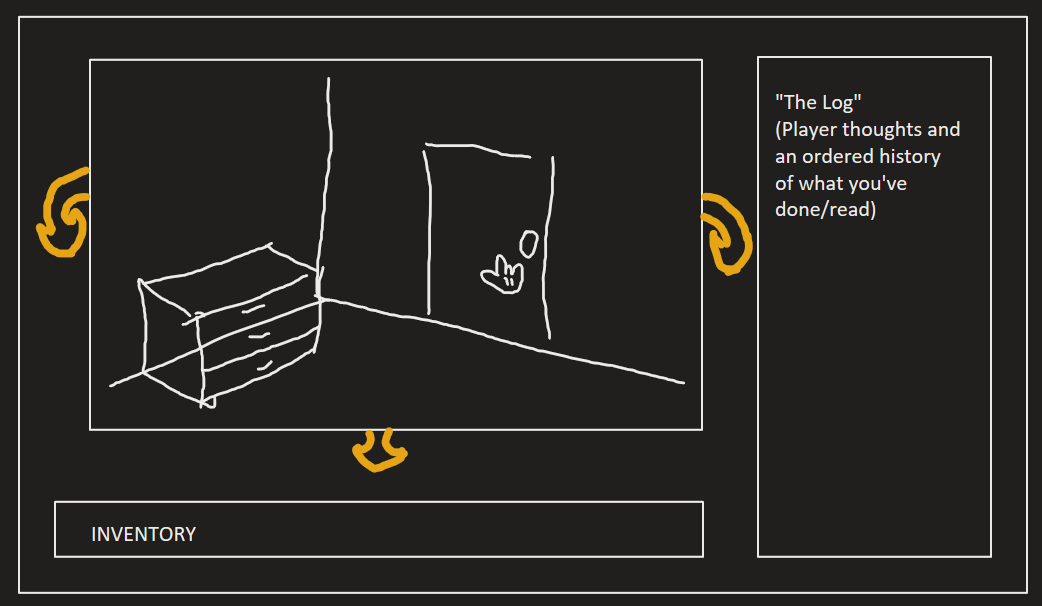

I also drew a couple versions of this during the ideation phase, which set a pretty clear path forward for what needed to be done, technically:

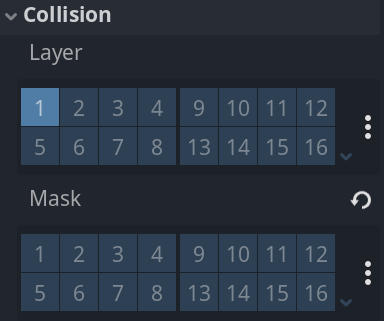

That "subwindow" meant that I needed to learn Godot's "viewport" system, despite my objections. This ended up being extremely useful when it came time to apply and swap viewport shaders, and I don't think things would have gone nearly as smoothly if I hadn't learned to make my viewport a TextureRect2D here.

I had already set my mind on this format before the story was a twinkle in Seren's eye, so I was also convinced we'd have more inventory-related puzzles. "Bring A to B, insert in order" deals, but we settled on using dial locks, which was good for me for other reasons. The inventory system was not nearly as robust as the log.

In the first week, I know I'd finished the basics of the click-to-navigate system (though, without turning) and I had the log populating and playing audio. I made a lot of mistakes with architecture here, thinking I needed a bunch of "manager" Globals, each acting as their own Signal busses, when most things can issue direct function calls to targets. Actually, this is a "Lessons Learned" deal. I'll make a header for it.

Call Down, Pass Up, Signal Broadly.

I have an unhealthy fixation with publish-subscribe models, because they attractively remove my responsibility to keep a reasonable, hierarchal flow of data in code. When there is an action that some piece of code may need to take in the future, and I don't know what object might hold that code, I make it a Signal. That way, instead of refactoring my code so the sender and recipient of the data hold the appropriate references, I can blast the Signal into the code ether and let God sort it out. Do not allow me to write code with more than 10 instances of a given object at a time.

Uncle Henry Isn't Home has 5 global signal busses, two of which were (correctly) made vestigial during development. The survivors are the GameDirector (which handles gamestate), ScriptDirector (which manages lines from our "screenplay", more on that later), and the AudioDirector (which takes calls from whoever asks to start/stop and queue sounds). Many of these signals are used only once, having no arguments but performing identical functions save for something that could have been an argument. I would make the argument that even the basic functionality of these could have been improved, because in almost every case that the ScriptDirector and GameDirector are called, they are being asked themselves to send Signals back down to subordinate nodes.

For instance: When the main game controller (a child of root) runs raycast checks for mouse clicks, it already has a reference to the ViewPort and gets a reference to the collider it clicks. In my ignorance and hubris, here I discard the collider (and it's very useful parent, which typically carries exports full of information about its functionality) and instead sends a Signal with a String back to the ScriptDirector with the name of the collided parent's "ScriptLine". The ScriptDirector then looks up this scriptline, and distributes its affiliated GameEvent, Log text and Audiostream names to their respective control scripts, also by Signal. All of these objects are singletons, there is no reason to think the Signal would reach anything except its lone target, and nothing else in the game has any reason to listen for these events.

This sounds ridiculous because it is.

I could have had the main loop hold a reference to the ScriptManager, and use a function within ScriptManager that accepts a reference to a "Clickable" (a collider's parent) and runs all the relevant functions by parsing the object and passing the relevant keys to the Log, Gamestate, Audio and Inventory singletons, which never change and which can mutually reference each other, should anything need to be passed both ways.

There were a few events that warranted Signals. One good example was "Puzzle Complete" events, which update the game state, play localized sounds, and alter several bits of the world at once. As I get better at planning out architecture ahead of acting on half-finished plans, this will be something to remember.

If the action required needs to be done by a single, static object, have members that need to use that function hold references to the static object.

If the action required needs to be done by the parent of many instanced children, give the children a reference to their parent and have them call the function directly.

Only if the action is a distributed collection of actions, done by a dynamic collection of unlike members with different functions, and requested by a dynamic set of objects elsewhere in the tree, should Signals be used. If you need to listen for any one of a scattered collection of emitters, and each receiver needs to do its own, special thing, then you can use Signals.

Time Management

I do not like managing projects. I knew from the initial discussion that this would be a lot of work to pack into 3 weeks. I had nothing else to do, and I wanted to see it through. In the end, everyone worked when they wanted and made what they wanted to make - at least I hope so. Save for my grinding and trying to check as many boxes off our list as I could, I put very few items on the to-do list for others, and when I did, it was only to fill in placeholders.

As a beginner, I don't have a strong picture of how long things take to do, and the more I do them, the shorter some tasks will get. The next time I have to plan a project, I still won't know how much time to allot to, say, greyboxing, because I won't be spending it reading boilerplate documentation for the engine and trying to remember that .basis is a child of .transform and not the other way around.

My goal in learning Godot is to close the loop between ideation and creation. I was frustrated by having ideas, knowing how they would happen, mathematically, but having no will to build applications from the ground up to try them out. Every time I want to act on a new idea, I learn a few new tools for it, and the learning adds time. A jam is a semi-safe place to lose time for the sake of learning, but when I don't know what time is required to learn a new tool, I can't plan ahead. This is how simple task like rotating a camera to the "nearest directional neighbor" becomes an all-day math problem, or adding a synchronized fade-to-black becomes a trip into the shader documentation.

This jam, I found it helpful to take breaks from the coding without taking breaks from the project. Our setting was begging for junk, so when I couldn't handle any more code, I started modelling furniture. We ended the jam with over 50 unique "furniture" objects, though some of those are posters and rugs. Some of my best work was the Victrola (which has a looping skeletal animation), the 4- and 6-faced dial locks (which use entirely procedural animation) and, of course, "Goobert", based on a sketch by Void.

In terms of personal time management, I found my best strategy was to redirect, rather than take a break from the project when I got frustrated or tired. It gave me a sense that I was always making progress, even when I wasn't checking things off my list, I could look at the Git history and see all the green plusses at the end of the day and know I'd added things.

I do not feel that our team crunched. I was working excessively in the second week, and certainly wish we could have had more of a complete game going into the third, but by Friday night, I was poking at annoyances (worse ones than the camera turning bug) and flipping idly between code, level finishing, and doodling in Blender. Normally, a project with a deadline is something I postpone work on until I'm desperate, but since I had been cranking away at the code factory full-time for the last 3 weeks, there wasn't a lot of desperation to go around. I think that I benefited from having a team, because they created expectations and generated feedback.

There's something very important to me about delivering asked-for, positive news that makes it easy for me to focus on work that will create it, for people I want to tell.

Test, test, test

This game was constantly broken in development. Every time I would finish fixing the last thing, someone would discover another problem that would lead me down another rabbit hole. The danger of trying to "robustify" and generalize every aspect of a game, is that as soon as one thing needs an exception, everything needs an exception, and if you've finally patched every hole, the engine will break.

Godot is a different machine depending on the platform. Our lighting and sound systems simply did not work in the web version, and I was determined to see this project runnable (and playtestable) with as little friction as possible. Worse, I implemented the lamp puzzle last of the 3, only to realize that Godot Web does not support the "Decal" object/shader used to project the paint texture on the wall. There went another hour of replacing and repairing.

Of all the things that I would have liked to fix, all the little annoyances I knew so well from starting and playing the game hundreds of times, I never got around to my longest-standing bug. Even though I knew what caused it, and why, and how I would fix it, I just didn't stop to do it.

Next time, I need to build test features into the game as a matter of design, not as 200 print() statements or a one-off hotkey that teleports me to a spot. All of the design work on the final area ("The Distortion") was done using a secret trigger in the front door, which I left myself notes to delete before publishing, because we had no easy way to test the transition to this segment in isolation. The secret trigger was just a duplicate of the real thing, which is locked inside a safe.

I know nothing about software testing. This is probably something to learn, both regarding the toolset available within Godot (@tool tags, live editable @exports, debug-only keywords) and to implement industry features and patterns.

The Bug that is a Feature

The code that turns the player's virtual head to match one of the pre-placed "head positions" is complex. It dynamically classifies and sorts the available transforms based on their relative similarity to the player's current view, and based on what direction about the local Y axis the player is requesting to rotate. It then sets the selected target, and every frame, closes 50% of the difference between the current view and the destination. This is bad practice for a number of reasons - framerate-dependence being one of them.

When the player requests to turn (not to move, only to turn) the game checks for the next head position in the requested direction, which is more than 0.01 radians away from the current position. If you are actively turning right, the target that you are turning to is still to your right until you have finished turning, so pressing the button additional times continues to set the target to what it already was. When you arrive within 0.01 radians of the target, it is no longer a valid right turn target, so the next position is selected and you can move again. The settling time to reach that tiny angle is relatively high - about 2 seconds is forever in UX - so players end up mashing the command, hearing the "footstep" sound but seeing no result.

This can (and will) be solved easily - when selecting the next target, use the current target as the comparison. Since the target transform is always equal to a valid position, the same math will disqualify its current location when selecting the "next right" position, and the player camera will continue interpolating to the next target in order.

The effect, unfortunately, is that the game feels quite drunk when you toggle rapidly between targets. It's certainly less frustrating to make about-faces, but the system still needs refinement to not look and feel... comical. This will be something to work on for a "cleaned-up", post-jam release.

Systems

Everything is a system. Games are systems. Complex systems are interesting. Therefore, the more complex a system is, the more interesting it is. That's why I built this game's code to be unreadable.

-Jergling, inventor of cruftbragging

At the outset of this project, I wanted to make something that was system-driven, extensible and broadly-applicable, in the way that an engine is, not a singular game. The blueprint for the project was about making a system that would work to tell Seren's story, but every decision I made, I tried to make as if I were designing a tool for someone else to make a first-person, point-and-click adventure game. Until I started running out of time. Then, I skipped all that and started making what I needed right then.

With some cleaning up, I would like to turn this game system into something like a proper template, with tools and a consistent structure designed to let artists and designers build the same kind of experience without much code. It's easy to make this kind of game in 2D - it's essentially a slideshow with hidden buttons, but the jump into 3D requires so much more processing and specification within the game. As it stands, the environment and basic exploration and dialog can be built with no coding knowledge, just a few templates for travel destinations and a JSON "screenplay".

The size of our game doesn't really show off the system, I'd really like to make something in this system with a lot of negative space and large structures with curving gravity. It all has the benefit of running in real-time - you can change lighting, play animations, run physics simulations, trigger spatial sound, and will all be consistent between viewpoints, because they're all viewing the same 3D world. While the trend right now is to do all exploration via the generic first-person walking controls, I think there's something very intuitive and human about the way point-and-click works. You aren't sliding a brick with a camera close enough to a puzzle to open a menu; you're crouching down to look at a hidden panel or feeling your way down a hall. The placement of the camera is deliberate, framed just as it is for the player's use and enjoyment, like a director lining up a shot to show (and leave out) exactly what belongs. I'd like to make more of that.

Closure

Now that the jam is over, and the scores are in, the team is all very happy with our placing. Even before the jam started, when things came up that were obviously out-of-scope, we were marking them down on the "full game" release. We know that some game jam teams love their product and their partners enough to make a commercial release of the jam game, but I don't think that's usually decided on before the team has worked on anything. Lucky for them, and I guess for me, we all seemed to enjoy the process and the end product. It felt very good to be recognized, and better to be satisfied with the outcome even without praise from peers.

Some of the team is eager to start on that full release. I've had a few too many hours of grinding at it, and I've started to build something else to reset. We are going to have a great time at the showcase on Saturday.

Get Uncle Henry Isn't Home

Uncle Henry Isn't Home

Find Uncle Henry. Lose yourself.

| Status | Released |

| Authors | Jergling, Seren Briar, spacedani2, Francisco del Valle |

| Genre | Adventure |

| Tags | Atmospheric, chicaghoul2025, Escape Game, First-Person, Horror, Indie, Point & Click, Singleplayer |

More posts

- Arcade Mode! (no, not like that)31 days ago

- Baby's First Video Game: Seren's Postmortem45 days ago

- Creating a Full Audio Experience for a Jam Game47 days ago

- Showcase Update49 days ago

Leave a comment

Log in with itch.io to leave a comment.